On the FRONT PAGE of the House & Homes section! (Saturday 01 March 2025)

Below is the online version:

Your Custom Text Here

On the FRONT PAGE of the House & Homes section! (Saturday 01 March 2025)

Below is the online version:

Images 1, 3 and 7 are of Chilham Castle in Kent

… we thought we’d feature this as Green Park (80 acres of woodland surrounding the house) is where our office is now based!

Aston Clinton House (Buckinghamshire Archeological Society)

Waddesdon Manor is probably the best known country house in Buckinghamshire but did you know there also used to be a Rothschild mansion in Aston Clinton where the Green Park activity centre is now situated? The mansion was demolished in the 1950s but old photographs show a sprawling neo-Georgian/Italianate house.

Aston Clinton House (Buckinghamshire Archeological Society)

The original house was built at some point in the late 18th century and by 1793 was owned by General Gerald Lake, an MP for Aylesbury and later 1st Viscount of Delhi, Leswarree and Aston Clinton. It remained with the Lake family until 1838 when it was purchased by the Duke of Buckingham. His son put it up for sale ten years later when it was described as a “most desirable brick-built and stuccoed sporting residence suited for a family of respectability”. It was eventually purchased in 1851 by Anthony Nathan de Rothschild. His wife Louisa apparently found the house too small so architect George Henry Stokes, son-in-law of Sir Joseph Paxton (best known for designing the Crystal Palace), was employed to extend it and a ‘Billiard Room building’, a new dining room, new offices and a new conservatory were added. Architect George Devey who worked on a number of other Rothschild properties including Ascott House near Wing made further improvements and also designed many estate cottages in the village and also the school and village hall, ‘Anthony Hall’ built as a memorial to Anthony by his widow Louisa following his death in 1876.

After Louisa’s death in 1910 her daughters Constance and Annie maintained the estate, spending a few weeks there each summer until the 1st World War, when it was lent to the War Office and became the HQ of the 21st Infantry Division who trained on the estate and the adjoining Halton estate which was owned by Anthony’s nephew Alfred de Rothschild. After the war, executors for the Rothschilds sold the estate in 1923 for £15,000. At the time it was advertised as a classical mansion with numerous reception rooms and bedrooms.

ASTON CLINTON HOUSE - School dining room (from an article by Diana Gulland in ‘Records of Buckinghamshire,’ 2008, where the photo appears courtesy of Hilda Isabel Marriott)

It was purchased by Dr Crawford, a schoolmaster who used the house as a boys’ school. Evelyn Waugh was a teacher for a short period but he was not enamoured with the house referring to it as “an unconceivably ugly house but a lovely park”. The school was not a success and, following a brief period as the Aston Clinton Country Club, it was once again put on the market and in 1933 opened as the Howard Park Hotel, ‘a first-class country hotel’ complete with a landing strip for aeroplanes. This too failed and it re-emerged as the Green Park Hotel in 1938, under new management.

ASTON CLINTON HOUSE - Ball Room (from 1923 Sale Catalogue of Mansion and Estate. By courtesy of Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society. From an article by Diana Gulland in Records of Buckinghamshire, 2008)

During World War Two the stables were used by the EKCO Radio Company as offices for the development of radar whilst the main house was used as a hospital for war wounded. Buckinghamshire County Council subsequently acquired the house and park in three lots from 1959 to 1967 with the proviso that it would be used for educational purposes. The house was demolished and the Green Park Training Centre built in its place. Today the only remnants of its existence are the balustrade, which once encircled the garden at the front of the house, the lodge in Stablebridge Road, the stables (used as part of the training centre) and the wooded parkland.

Plan of Lot 1 - from 1923 sale Catalogue of mansion and estate - Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society (from article, ‘Aston Clinton House 1923-32’ by Diana Gulland, Records of Buckinghamshire, volume 48)

GENEALOGY FOR BUILDINGS

By Patrick van Ijzendoorn - UK & Ireland correspondent for Dutch national newspaper, De Volkskrant, and Elsevier Weekblad

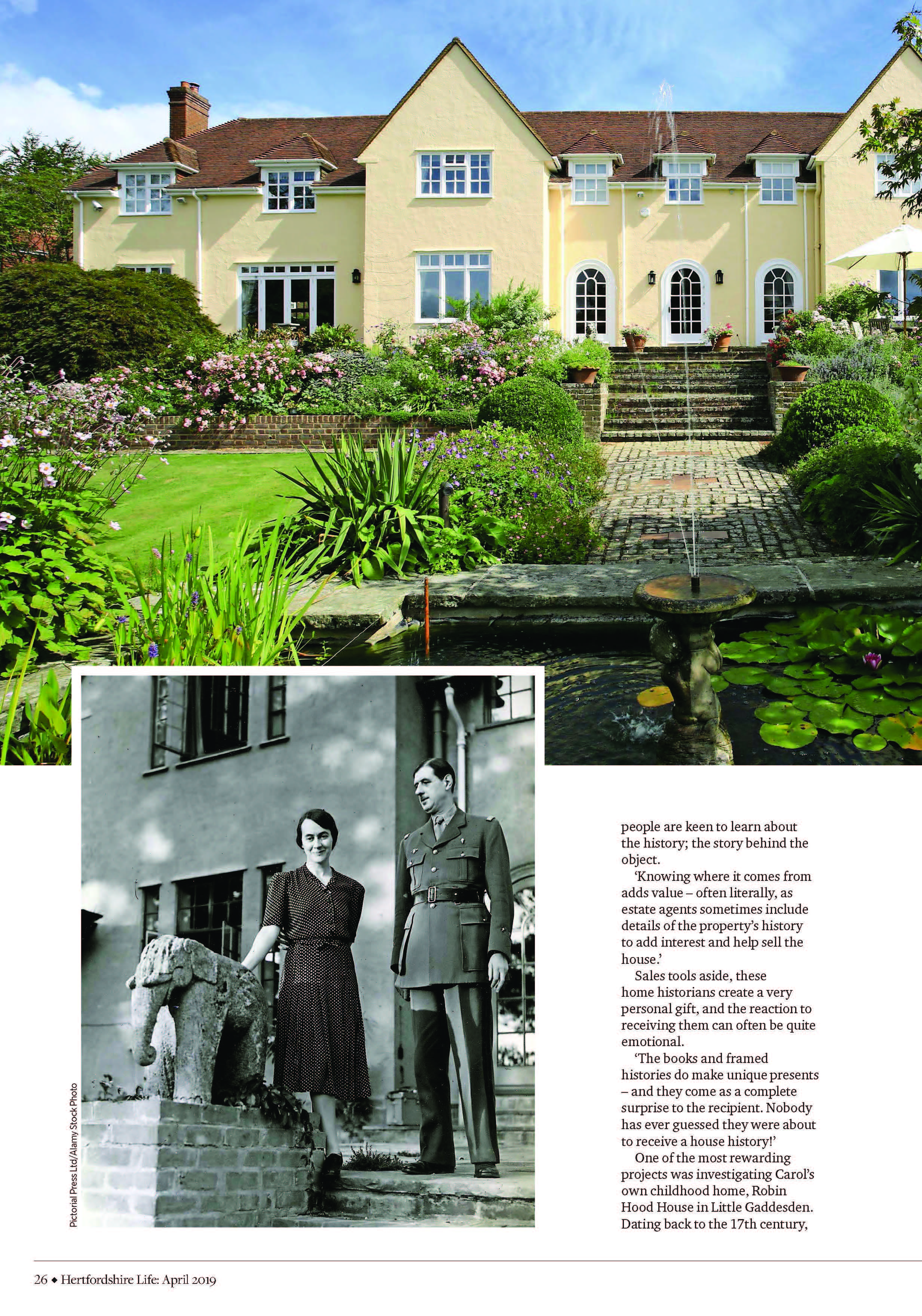

When Lynne Caulfield bought the Low House last year, she wanted to know everything about the history of this age-old farmhouse in the English village of Ivinghoe. It was not easy - Google and the municipal archives did not take this amateur historian a step further forwards. “Coincidentally, one day a brochure fell on the doormat”, she says, “from Benchmark House Histories, a company that helps homeowners with historical property research: genealogy for buildings”.

“It is a growth market”, says Anglo-Dutch photographer Carol Fulton, who collaborates with historian and genealogist Cathy Soughton. On request, the two make books about the history of a particular house. "We have been doing this for nine years and we are seeing more and more interest. Some people just want to know everything about their house, others think it is an original birthday gift for their partner. It can also increase the value of a house to sell. "

“A customer was seeking”, says home detective Soughton,”a historical explanation for paranormal appearances in his home. Another knew she lived in what was once the home of Churchill's wife and wanted more information. Sometimes the two make unexpected discoveries. Fulton: "In a bedroom of a holiday home we were investigating, it turned out that a suicide had been committed. At the client's request, we omitted that fact from the book."

It was a great revelation for Caulfield: "Carol and Cathy discovered that my house was originally the home and workplace of a cartwright, then it was a rectory, a cane maker’s home and, in Victorian days, a tailor lived there. The latter also explained the atypical bay window, probably built to advertise. Old masters have also lived there, we now know, and a cabbage dealer. The house has come alive, you can feel the presence of the earlier residents."

It has not stopped with a coffee table book. A sign with ‘Wheelwrights House’ has recently been added to the facade.

* * *

We have a lovely feature in the current (April issue) HERTFORDSHIRE LIFE magazine - by Laura Vickers

Walk down most High Streets nowadays and you’ll find plenty of cafes and coffee shops where you can pick up your favourite espresso or cappuccino, but have you ever wondered how long coffee shops have been around? We may think that they are just a recent phenomenon but coffee houses have actually been in existence in this county since the 17th century, although back then they were men only meeting places for business and political or literary debate.

Coffee was first introduced to England in the 17th century from Turkey. Originally viewed as a medicinal plant and an acquired taste - one early sampler likening it to ‘syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes’ - it quickly became popular. Coffee was drunk black and sweetened with sugar, but milk was not added. The first coffeehouse in England was opened in Oxford in 1650, followed soon after by one in London. Soon they were commonplace in larger towns. By 1675 there were more than 3000 coffee houses throughout England with a large number in London but also in the provinces. Given the Turkish connection, a popular name for coffee houses was the Turk’s Head but other included Garraway’s, Batson’s and even a Nando’s!

17th century coffee house

Coffee houses became known as places to debate matters of politics, science, literature, commerce and religion, so much so that some in London were known as ‘penny universities’, as that was the price of a cup of coffee. Several British institutions can trace their roots back to coffee houses including the London Stock Exchange, Lloyds of London and Sotheby’s and Christies auction houses. Influential patrons included Samuel Pepys and Isaac Newton. Anyone (as long as they were male) could frequent them, and some became associated with republicanism, leading King Charles II to attempt to ban them in 1675, but the public outcry was such that it was quickly withdrawn. However other coffee houses were not so illustrious and were haunts for criminals and prostitutes.

Although some coffee houses had female staff, women were not welcome as customers and the rather tongue in cheek pamphlet published in 1674 called the Women’s Petition Against Coffee complained how the ‘newfangled, abominable, heathenish liquor called coffee’ had transformed their industrious, virile men into effeminate babbling layabouts who idled away their time in coffee houses!

The coffee house fell out of favour towards the end of the 18th century as the new fashion for tea replaced coffee. They were revived in a slightly different format in the later Victorian period by the Temperance Movement which promoted abstinence from the consumption of alcohol and looked to provide other forms of entertainment to tempt people away from pubs. A number of coffee taverns were established as a result and they became a common addition in towns and larger villages.

After World War One the Temperance Movement declined and consequently the popularity of coffee taverns. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that coffee houses were reinvented by the likes of Starbucks and Costa Coffee – who knows though what 17th century patrons would have made of a decaf skinny caramel macchiato!

Cathy Soughton - June 03 2018

We haven’t produced a full house history of Claydon House (that would be an amazing book to do!) but this is from an article that Cathy wrote for a local magazine.

Described as an “unexpected Georgian jewel tucked away in the Buckinghamshire countryside”, Claydon House, now run by the National Trust, is an 18th century country house near Middle Claydon that was built by the Verney family to showcase their wealth. The building did not turn out as originally planned but its sumptuous interiors and a museum to Florence Nightingale who was a frequent visitor make it a fascinating visit for all the family.

The current Claydon House was built by Ralph 2nd Earl Verney between 1757 and 1771. The Verney family has lived at Middle Claydon since 1620 and renowned members include

Sir Edmund Verney who was King Charles 1’s chief standard bearer during the English Civil War. Sir Edmund was killed at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642, and according to a family story, the standard was found clutched in his severed hand, although his body was never recovered. His son Ralph initially supported the Parliamentarians but became disenchanted and sought exile in France. In 1661 following the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II awarded him a baronetcy and he later became MP for Buckingham. His grandson Ralph was created an Earl in 1743. One notorious Verney was Edmund’s half-brother Francis who, unhappily married and pursued by creditors, left England for Morocco and converted to Islam. He became a feared Barbary pirate until he was eventually captured and spent two years imprisoned as a galley slave. He was freed by an English Jesuit on the promise that he would convert to Catholicism which he did but died soon afterwards.

Ralph the 2nd Earl planned on enlarging his late 16th century mansion at Claydon into an enormous dazzling Palladian country house which would rival nearby Stowe House. The new house was to have two large wings, one including a ballroom, with a huge domed rotunda in the centre of the building. Work started in 1757 but it proved troublesome and Lord Verney ran into financial difficulties and he died bankrupt in 1791. His niece Mary Verney inherited the estate and subsequently demolished the uncompleted north wing and centre leaving just the west wing which remains today.

The exterior of the house is quite unassuming; built on classical lines it consists of two floors, over seven bays, with the middle section having a pediment. Fortunately the interior of the wing was left intact and in contrast is extraordinarily grand featuring intricate ornate and lavish Rococo carvings and plasterwork. A highlight is the wonderfully exotic Chinese room on the first floor which features a carved pagoda inspired alcove and walls and doorways encrusted with chinoiserie – a Chinese inspired decorative style. On the first floor there is also a museum to Florence Nightingale, the sister of the wonderfully named Parthenope Nightingale who had married Harry Verney in 1858. Born as Harry Calvert, he had changed his surname by royal licence in order that he could inherit the Verney estates from his cousin Mary Verney. Florence was a regular visitor to Claydon House and did much of her writing there as well as entertaining groups of nurses who came out from London for tea parties and breaks from their training. Her four poster bed is still at the house and children can try it out for size.

The house was given by the Verneys to the National Trust in 1956 but the current 6th Baronet, Sir Edmund Verney still lives there. Now open to the public along with attractive gardens, parkland, the adjacent parish church and courtyard businesses there is plenty to do for all the family with regular special events taking place, see the website https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/claydon for more details.

Tucked away close to St Mary’s parish church in the pretty village of Long Crendon in south west Buckinghamshire near the Oxfordshire border, is a beautiful medieval Court House which dates from the 15th century. Now owned by the National Trust it is open to the public and is well worth a visit.

The Court House at Long Crendon

The Court House is a long 5 bay, 2 storey timber framed jettied building. It was previously thought that the court house was built in the early 1500s but recent dendrochronology tests using tree ring dating on some of the original beams show that they were felled between 1483 and 1487 so it was almost certainly built between these dates. It is believed that the building originally served as a church house – the medieval equivalent of the church hall, and would have been used to celebrate religious festivals and ‘church ales’ which were social gatherings to raise funds for the church where strong ale was brewed and drunk on the premises. Such festivals would originally have been held in the church itself but as pews were introduced into churches in the later medieval period, lack of room led to separate church houses being built.

The Puritans disapproved of such merriment (alcohol was permitted but not to excess!) and under Oliver Cromwell’s rule in the 1650s church ales and festivals were banned. Redundant church houses were often converted into pubs or schools but in the case of the Court House at Long Crendon it seems it was used for a period to store and sell wool (it was once referenced as 'Old Staple Hall') and the upstairs room was used to hold regular manor courts (although the building may well have also been used for this purpose since it was first built).

In the 1200s the manor of Long Crendon which had been held by the Earl of Pembroke was divided between three female co-heirs. By the 1500s, the three respective Lords of the Manors were the Dromer family who were Wycombe wool merchants, St George’s Chapel in Windsor and All Souls College in Oxford. The latter two institutions held a number of manors in the area. Manor courts were originally held to administer the customs of the manor and deal with any civil disputes and minor crimes and offences such as selling rancid fish and unlicensed beer. All tenants in the village would originally have been expected to attend the courts but by the Tudor period manorial courts mainly just dealt with property issues and the transfer of copyhold land. Under the feudal manorial system all copyhold land whilst in practice owned by the tenant was formally owned by the lord of the manor and each time copyhold land was sold or passed to an heir the new tenants had to go before the court to be formally admitted. Whilst a lot of copyhold land was enfranchised during the 19th century the system essentially remained unchanged until the 1920s when the 1922 Law of Property Act abolished copyhold tenure.

In practice the Long Crendon courts for each of the three manors were probably held at the same time (at least annually if not more frequently) and would have been administered by a locally appointed steward who represented the three Lords of the Manor. Records of the three Haddenham manors have survived well (the earliest records date from the 13th century) and are held respectively at the Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies, the Bodleian Library in Oxford (All Souls College records) and St George’s Chapel in Windsor. As copyhold land was often inherited they can be a really useful source in providing genealogical information for family historians.

The manor courts would have been held on the first floor of the building which as is now, was one large long open room with a small adjoining room, used at one point as a kitchen. The exposed roof beams are a key feature of the room and comprise five bays of alternating tie beams and arch braced collar trusses. The upper story is jettied on the south and west sides. The east end is in the Wealden style (a type of medieval house common in Sussex and Kent where a recessed open hall was flanked by floored jettied end bays) although in this case the east end itself is recessed and it appears that it originally was open from the ground floor. There was a large fireplace at this end with a 16th century moulded wood lintel which ran the full width of the building.

On the ground floor each bay was separated to form individual rooms which by the 18th century were used to accommodate the homeless poor in the parish. In this period each parish was responsible for providing parish relief for those of its residents who had fallen on hard times. In many villages a building was used to house those parishioners, often the elderly, who had no other means of support and the Court House in Long Crendon would have served a useful purpose. In 1834 with the introduction of a new Poor Law Act the system changed and all local able bodied persons who couldn’t support themselves were sent instead to the new Union Workhouse which was built at Thame. As a consequence the lower rooms were rented out to tenants although the upper floor continued to be used for the Manor Court meetings and was also used by the local Sunday school. However the building by this time had fallen into disrepair and was threatened with demolition. The vicar mounted a campaign to save it and following a survey by the recently formed National Trust the organisation decided to buy it – the second property they acquired. It was restored in 1900 at a total cost of £560. The upper floor continued to be used to hold the manor courts until they were finally abolished in the 1920s whilst the ground floor was let to tenants.

The Court House (upper floor only, accessed by very steep steps) is now open to the public on Wednesdays, and weekends. More details can be found on the National Trust’s website: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/long-crendon-courthouse/

In the parish church at Whitchurch in Buckinghamshire is a striking marble monument to John Westcar who died in 1833, by the sculptor John Gibson showing a gentleman attired in a Roman toga standing in front of a bull and some sheep. John Westcar was considered to have been the most extensive grazier in the country at the time and bred cattle at Creslow.

John Westcar monument at Whitchurch

John was baptised in Cottisford, an Oxfordshire parish a few miles west of Buckingham on 23rd October 1748, the son of John and Joanna Westcar. John senior was a wealthy grazier (a farmer who reared cattle or sheep for market) whilst Joanna came from a prominent Northamptonshire family and was Great-Aunt to Lord Sidmouth, the Prime Minister from 1801 to 1804.

John junior followed in his father’s footsteps and also became a grazier. He spent his early adulthood at Mixbury in Oxfordshire where his father was farming when he died in 1784. John married Mary Hedges of Creslow, daughter of Thomas Hedges a grazier, at Cublington parish church on 22nd March 1780 by licence. The marriage licence bond records John as being a Gentleman of Mixbury. The Hedges had farmed at Creslow for much of the 18th century and it seems that following John’s marriage to Mary, he took over as grazier at Creslow and leased several hundred acres of land from the Earl of Clifford who was the lord of the Manor of Creslow at the time.

The Creslow pastures were renowned for their exceptional fertility and were considered to be the finest in the county. At the dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, the Manor of Creslow was then in the hands of the Knights Hospitaller. The King appropriated the land and the pastures were used for feeding cattle for the Royal household up until the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell. The Cliffords subsequently acquired the land in the 1670s.

The Westcars lived in the 14th century manor house at Creslow, one of Buckinghamshire’s oldest continually inhabited buildings. Originally there was a church at Creslow which adjoined the manor house but during Queen Elizabeth's reign, services ceased to be performed and it later was used as a dovecot. John Westcar adapted it to serve as a coach-house by the insertion of partition walls and upper floors.

John specialised in breeding Hereford cattle and as early as the 1770s he attended the Hereford fairs to purchase cattle which he bred on the Creslow pastures and sold at markets including Oxford and London. On occasion it was reported that he visited the fairs with Francis the fifth Duke of Bedford who was greatly interested in agriculture and later became the first president of the Smithfield Club. The pastures included the “Great Field” which comprised 310 acres of undulating ground and in the summer months John reportedly kept over 200 large oxen and up to 500 sheep and lambs and around 20 mares and foals. At the time, there were large elm trees on one side which gave shade to the animals.

He was one of the founding members of the Smithfield Cattle and Sheep Society (later known as the Smithfield Club and now as the Royal Smithfield Club) which was formed in 1798 with the aim of improving and promoting the breeding of cattle, sheep, pigs, poultry and other livestock. At the first annual Royal Smithfield Show held in 1799 he won first prize for one of his oxen which sold for 100 guineas (over £5000 in today’s money) and reportedly weighed in at nearly 250 stone. Some of the oxen were fed on turnips and hay, (grass fed) whilst others were fed on oil cake and corn. Newspapers at the time reported that he regularly won prizes at shows over the next 20 years (at least 42 in total at Smithfield).

John pioneered the transport of cattle by canal. The opening of the Grand Junction Canal (later the Grand Union Canal) as far as Marsworth by 1799 made it a much easier method of transporting cattle to the London markets rather than using the old drovers’ roads although in the early days transportation by canal had its problems. Dry summers led to shortage of water in the canal and it was reported in The Morning Chronicle in 1802 that “Mr Westcar’s large oxen were intended to come from nearest point of the Grand Junction Canal to his farm, then by a barge to Paddington Wharf, but the shortness of the water on the summit at Tring, by which the public have, during this and the late summers suffered so much, prevented it, and the oxen were obliged to be driven to Two Waters wharf [Hemel Hempstead], where they were put into a barge and conveyed to Paddington.”

In 1831 John had his portrait painted by artist and engraver Charles Turner who had been appointed "Mezzotinto Engraver in Ordinary to his Majesty" in 1812. The portrait is now in a collection at the National Portrait Gallery.

John Westcar by Charles Turner, 1812

Although he amassed a fortune from the sale of his stock, in his personal life he had some tragedy. He and his wife Mary had one child, a daughter Mary who was baptised on 27 February 1781. Sadly Mary the mother died soon after the birth and was buried on 24 March 1781 at Whitchurch. John never remarried. His daughter Mary later married a naval Captain Edmund Turberville in 1819 at Whitchurch but they did not have any children and the marriage ended in divorce in 1835 due to Edmund’s adultery. Divorce was rare in this period and in England could only be granted by a private Act of Parliament. Mary appears to have circumvented this by applying to the Court of Session in Scotland for a divorce which was subsequently reported in several papers including the Bucks Herald.

John died on 24th April 1833 aged 84. The Bucks Gazette reported that he was found dead in one of his fields having fallen from his horse. He had apparently recently complained of frequent giddiness in his head. 6 months before he died he made a lengthy will running to some 18 sheets of paper. It shows that he was an extremely wealthy man when he died. He left money to a large number of beneficiaries including an annuity of £100 (now around £5000) to his faithful servant Mary Lake and £1 each to every labourer who had been employed by him in the 12 months preceding his death. He left an annuity of £2000 to his daughter Mary which he trusted would be sufficient given that he gave her £10,000 (around £500,000 in current terms) when she married Edmund Turberville. His nephew Henry Westcar was left £2000, his portrait and other annuities whilst another nephew Richard Rowland was left £5000 and his lease in the farm at Creslow. The Rowlands subsequently farmed at Creslow until well into the 20th century. John also left three sums of £500 in trust with the annual income to be used to buy clothes to be given to the deserving poor in Whitchurch, Cublington and Souldern in Oxford.

John also specified in his will that he was “to be buried in as private a manner as possible in the parish church of Whitchurch near to the remains of my late wife and (if my Executors think it right) to have a handsome monument erected over the seat I usually sit in when at Church to the memory of my late wife and myself and I hope and trust my friends the Reverend Thomas Archer of Whitchurch and the Reverend Henry Bullen of Dunton will assist my Executors with their advice in the erection and execution of the said Monument and when my friends shall have had what writing and engraving they think necessary to be put on it I beg the two following lines to be engraved underneath:

Unblemished let me live or die unknown!

Oh grant an honest fame or grant me none”

Obviously John had his wish and a handsome memorial was erected – hopefully he would have approved of it!

Situated in the small village of Boarstall in Buckinghamshire, close to the Oxfordshire border, Boarstall Tower is a superb medieval moated gatehouse that has a fascinating history. Now a Grade 1 listed building it is owned by the National Trust and is open to the public during the summer months.

On 12th September 1312, Edward II granted John de Haudlo, the lord of Boarstall Manor, a licence to crenellate (fortify) his mansion house with a wall of lime and stone. Dendrochronology tests on internal beams using tree ring data show that these were felled in 1312 so construction must have started almost immediately. Although designed as a defensive building, the gatehouse was very grand for its time and de Haudlo probably built it largely as a status symbol. Whilst not a true castle, it copied the style of recently built castles such as Caernarfon Castle in Wales and features include arrow slits, gargoyles and battlements.

The Tower was originally approached by a drawbridge over the moat but this was replaced by a wooden bridge in 1615 at the same time as new windows were inserted and the roof raised. With any perceived threat of attack long since passed, it was probably the intention to convert the tower into a hunting lodge. However less than 30 years later, Boarstall was the centre of heavy fighting in the English Civil War between the Royalists who had their stronghold at Oxford and the Parliamentarians who had a base at Aylesbury. In 1643 the Royalists built a garrison at Boarstall, but it was abandoned the following year and the Parliamentarians took possession. Realising it presented a threat to their Oxford base, the Royalists recaptured it in June 1644 having ‘battered the house with cannon’. A year later on 1st June 1645 the Parliamentarians New Model Army attacked Boarstall with 1200 men and used 120 scaling ladders but the Royalists fired ‘so thicke upon them’ that they withdrew leaving all their ladders behind. Contemporary reports suggest that the Parliamentarians lost between 120 and 300 men whereas the garrison only lost just one out of 100 men.

The Royalists subsequently demolished the church and all the houses in Boarstall village to prevent the Parliamentarians using them for cover, leaving just Boarstall House, the Tower and the adjacent farmhouse. In the spring of 1646 the Parliamentarians besieged the garrison for nearly 10 weeks. The garrison commander Sir William Campion only surrendered on 10th June having heard that the King was about to surrender at Oxford. There are still signs of cannon damage above the entrance to the Tower but overall there is little visible evidence of the fighting.

Boarstall House, the medieval mansion behind the Tower, was demolished in 1778 by Sir John and Lady Aubrey, a year after their only child, a son aged 6, died from ‘eating contaminated gruel’. This was most probably ergotism, a disease caused by eating infected rye grain which causes convulsions and hallucinations and which it is now believed explains certain ‘bewitchments’. Fear of witchcraft was prevalent in this period and the Aubreys evidently thought the house was cursed and must be demolished. They subsequently moved to Dorton House in Dorton, now Ashfold School.

The Tower remained unused until 1925 when it was converted into a house and the gardens reconstructed. In 1943 it was sold to the National Trust who restored it in 1998/9. It is now tenanted and open to the public on selected dates. For opening hours visit: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/boarstall-tower/

Thanks to Rob Dixon for providing information and photos.